George Washington is one of the most well known political and historical figures in the world. The Founding Father was a General & The Commander-in-Chief of the Colonial Armies during the Revolutionary War. He then went on to become the first President of the United States as we all know. Counter to popular belief, Ol George didn’t wear a powdered wig nor did he have wooden teeth (he did have dentures made out of hippopotamus ivory, other human teeth, and metal fasteners though. So, still pretty unsightly)!

While President Washington is a fascinating and prolific character, it’s the man who had his ear you’ll read about today. The man who made a retired George Washington an overnight whiskey tycoon.

James Anderson grew up on his father’s farm about 40 miles north of Edinburgh, Scotland learning the trade of cultivating land. At the age of twenty-one Anderson took a farming apprenticeship and within two years was managing an entire estate. After only three years in that position, he started and ran his own farm, mills, and distillery for nineteen years. In this span of time, James married Helen Gordon who was from the nearby village of Inverkeithing and had seven children. News of life and opportunity in the new country across the ocean had saturated Scotland, so by the early 1790’s Anderson’s family made the long journey to Virginia.

Upon arriving, Anderson rented a farm in Fairfax County and managed other people’s farms for the next several years. Then, in October of 1796 he was hired as a farm manager for none other than sitting President, George Washington.

Armed with his experience from Scotland, Anderson immediately saw an opportunity to maximize Washington’s resources in a way not previously realized. To maintain healthy soil, Washington utilized a significant amount of rye as a “cover crop”. Rye, not typically considered edible, would generally go to waste. With the availability of these large amounts of grain paired with access to a gristmill and good source of water, it was obvious to Anderson. He could make whiskey.

I would love to have been privy to that first conversation. Jame’s pitch to Washington with perhaps his only context of his boss’ relationship with whiskey being his role in the “whiskey rebellion” only a few years earlier. President Washington had recently left office and said in a letter to James,

“I am once more seated under my own Vine and fig tree, and hope to spend the remainder of my days—which in the ordinary course of things (being in my Sixty sixth year) cannot be many—in peaceful retirement…”

After hearing his manager’s proposal and seeking the counsel of a friend in the rum business (as any good businessman ought to do), Washington couldn’t ignore his entrepreneurial spirit and was on board. Shortly after this, Washington wrote to a friend,

“Mr. Anderson has engaged me in a distillery, on a small scale, and is very desirous of encreasing it: assuring me from his own experience in this country and in Europe, that I shall find my account in it.”

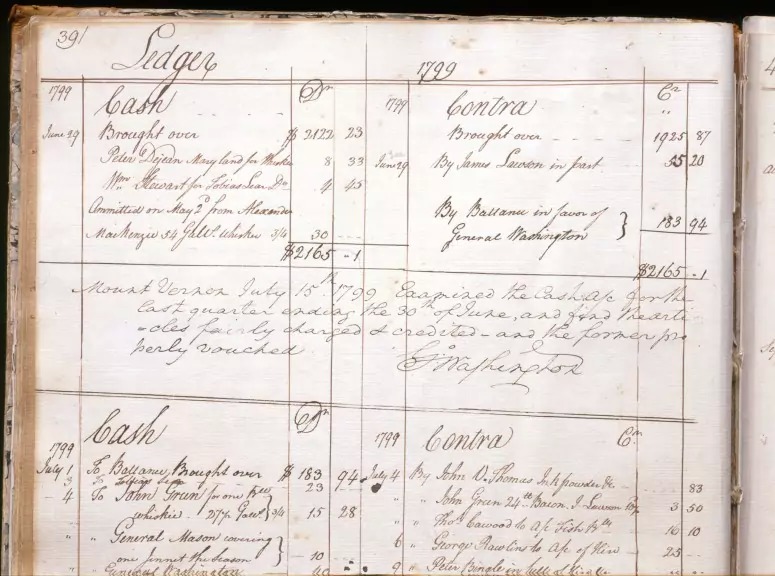

The first run of spirit was so successful that Washington ordered the construction of a full scale distillery, brandishing 5 stills. The distillery was complete in 1798 and in only a year was the largest whiskey distillery in the country! Not surprisingly, many of the operations first customers were folks close to Mount Vernon. According to a surviving ledger, the duo distributed 11,000 gallons of clear, un-aged whiskey worth about $7,500 that year. If that doesn’t sound like a lot, that’s somewhere in the neighborhood of $150,000 by current standards. Not too shabby!

You may be asking yourself, “Why didn’t whiskey-maker find its way into George Washington’s list of go-to titles?”

Our first President died in 1799, and when he did he left the distillery to his nephew Lawrence Lewis. Unfortunately, Lawrence was not quite the businessman that his uncle was and the business found far less success under his leadership. Shortly after, in 1802 Martha Washington also passed away and this also marked the end of James Anderson’s management of Mount Vernon and it’s operations. Then, in 1814 there was a fire that left the distillery burned to the ground. It was not rebuilt. Not for a long time, that is. In the early 1930’s, the state of Virginia bought the site and rebuilt the gristmill and miller’s cottage, but not the distillery (mostly due to the pressures of prohibition and the depression).

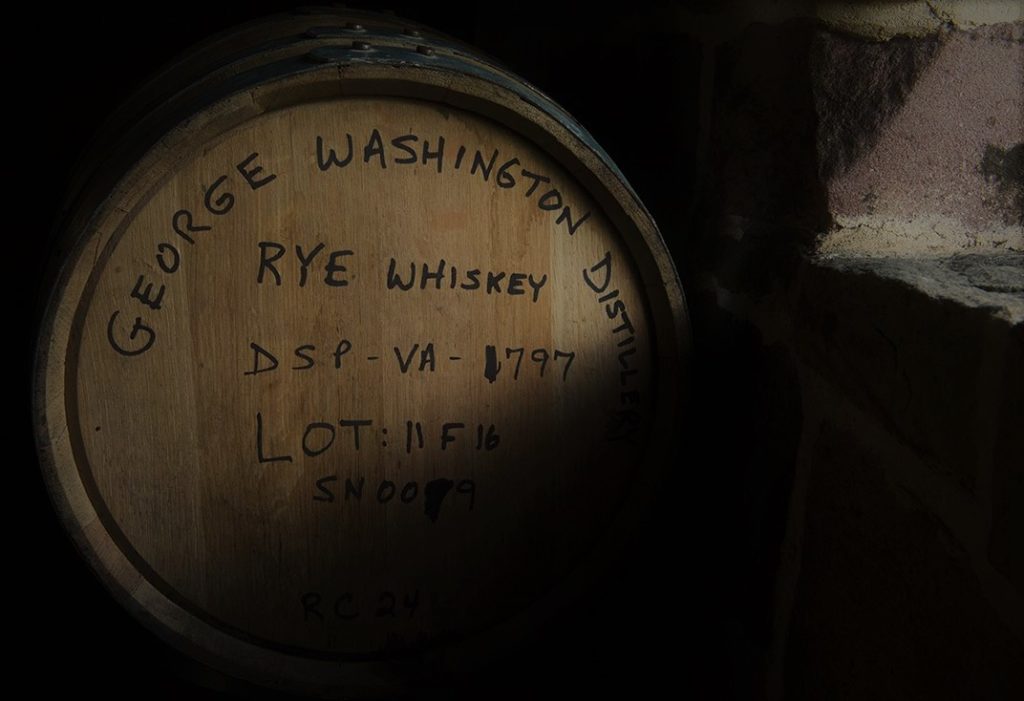

It wasn’t until 1998 that archeologists discovered the foundation on which the original distillery stood and started making plans to resurrect it. With a desire to rebuild based on original designs, a group of archeologist, historians, and distillers went to work researching the distillery that had been forgotten with funding from the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS). They combed through records looking for answers to questions like: “what role did it play on the estate and 18th-century America?” and, “How did it function and operate?”

from mountvernon.org

Finally in 2007, more than 200 years later, the distillery was once again open to the public. Not only does it stand as a monument to the business-savvy Washington and his partnership with James Anderson, but as a fully functional distillery with a small team producing whiskey just as Anderson did in its hay-day. 65% rye, 35% corn, and 5% malted barley distilled in 18th century style copper stills heated by a wood fire and cooled by water from the nearby creek.

Plan your trip at www.mountvernon.org